Invasive species come in many forms and can be native or nonnative. Florida is known for its beautiful waterways and marshlands, so invasive aquatic plants are particularly threatening to Florida’s environment. In Crystal River, there are four main invasive aquatic plants: water hyacinth, water lettuce, hydrilla, and lyngbya.

Water Hyacinth and Water Lettuce

Both water hyacinth (left) and water lettuce (right) are nonnative to Florida and originated from South America. When cargo ships travel between South America and Florida, they can carry invasive plants in their ballast water. When the ship reaches its destination and releases its ballast water, any foreign plants trapped inside gets released into a new ecosystem. (Cargo ships take water in their ballast tank to enhance maneuverability and stability on the water. When ships reach their destination, they pump out the foreign water, which contains foreign substances. For more information, visit here.)

When Crystal River had fewer manatee, water hyacinth and water lettuce dominated waterways because the plants could thrive in the warm climate and had few predators. By rapidly reproducing, water hyacinth and water lettuce form dense greenery at the surface of the water and prevent light from reaching the plants below. Light is a critical ingredient for photosynthesis and without it, plants die. This process results in a monoculture of invasive plants that outcompete native plants.

Thankfully, manatee love water hyacinth and water lettuce, and as manatee populations have risen in Crystal River, likely a product of increased food sources (eelgrass) and conservation efforts, water hyacinth and water lettuce levels have greatly reduced. Also, water hyacinth and water lettuce are relatively easy to remove since they float on the surface of the water and can easily be scooped out. Sadly, hydrilla and lyngbya aren’t as easy to control.

Hydrilla

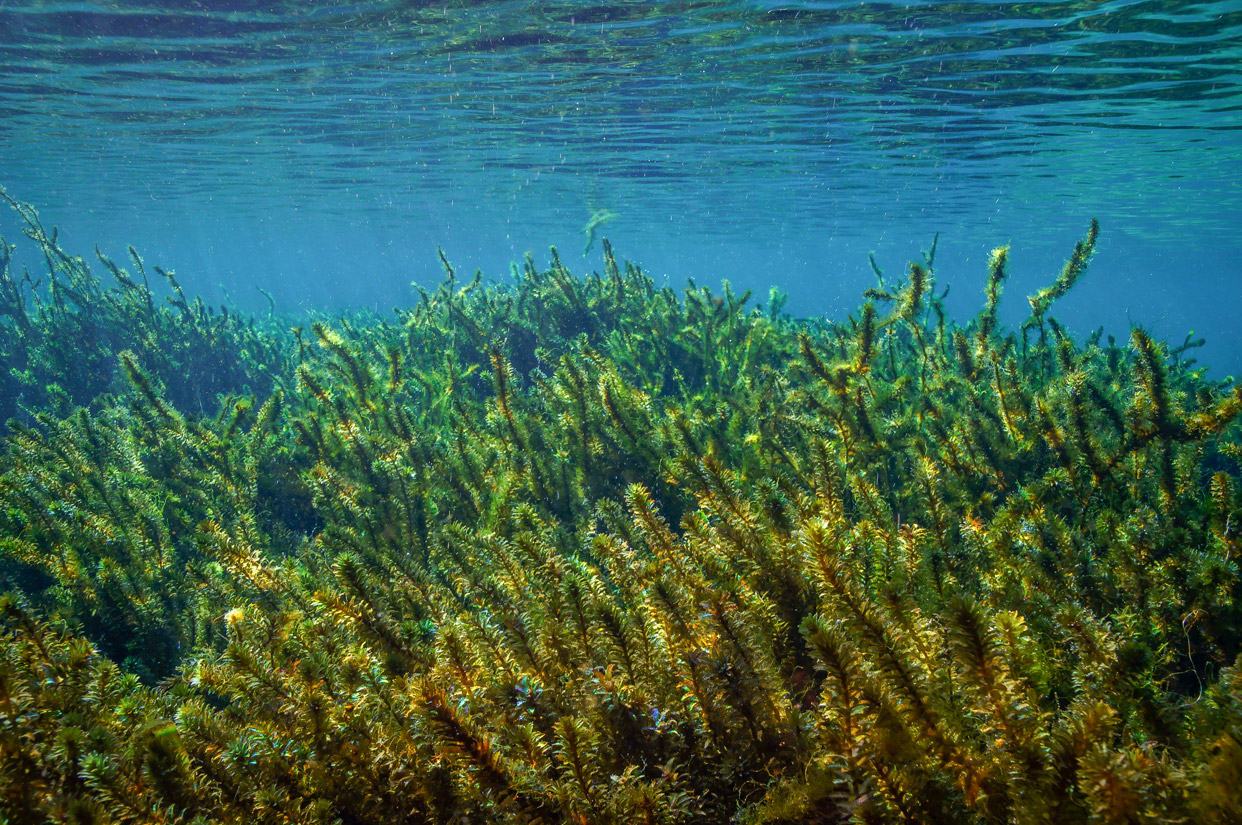

While manatee eat hydrilla (above), hydrilla is much more invasive than water hyacinth and water lettuce. Hydrilla is native to Asia and was spread worldwide in the aquarium trade. If you look at the image at the top of this article, you can see why people wanted hydrilla in their freshwater fish tanks – it’s symmetrical and pretty when it flows in the water. Also, just like water hyacinth and water lettuce, hydrilla travels in cargo ships and can spread into new regions as a result of trade.

Hydrilla is extremely invasive because even small fragments of the plant can grow into full sized plants. Anyone who carelessly dumps out their fish tank into open waterways can easily introduce hydrilla into a new ecosystem.

Another aspect that makes hydrilla so invasive is the fact it can live in a variety of water qualities. If you’ll recall from a past blog linked here, pH, salinity, turbidity, etc. determine water quality. Hydrilla is one of the most invasive species in the world, and it is found on every continent except Antarctica.

Hydrilla, like water hyacinth and water lettuce, forms monocultures by rapidly reproducing and outcompeting native plants. Once hydrilla grows large enough, it will stretch from the riverbed to the water’s surface. At the surface, hydrilla forms dense greenery, which blocks the sun from reaching plants below (see image below).

What Have We Done About Hydrilla?

Removing hydrilla is extraordinarily difficult and costly. Hydrilla grows faster than manatee can eat it, and whenever a manatee breaks a hydrilla plant, the broken plant fragments can form new plants.

The name “hydrilla” originates from the Latin word “hydra,” which has two different meanings. The first definition of hydra refers to the many-headed beast in Greek mythology. When one head of the hydra is cut off, two grow back. More modernly, Hydra means an evil that can’t be overcome by a single effort. I’d say hydrilla fits both of these definitions.

Hydrilla is known to completely take over waterways and to prevent any navigation by manatee or human. The fact that hydrilla is present throughout King’s Bay is worrisome because if left unregulated, King’s Bay could eventually look like the image above.

In the past, people tried to eliminate hydrilla by poisoning it, which was costly and risky. In King’s Bay, poisoning worked and the hydrilla died, but it made the overall situation worse. As hydrilla died, it sunk to the riverbed and contributed to the thick layer of muck. This muck created an anaerobic environment where rooted plants, like eelgrass, could not effectively survive.

Poisoning, combined with the massive amounts of saltwater that flooded into Crystal River from the No Name Storm on March 13, 1993, led to the death of tons of hydrilla and added to the mucky, anaerobic riverbed.

How To Combat Hydrilla

There are only a few effective ways to prevent devastating levels of hydrilla.

1: Catch hydrilla early. If we notice hydrilla growth early enough, we can prevent if from getting out of control.

2: Manatee eat hydrilla, so if the hydrilla isn’t overwhelming, manatee will be able to graze and reduce hydrilla density.

3: Plant eelgrass properly. Mature and properly planted eelgrass outcompetes hydrilla. If you swim in Kings Bay, you rarely see hydrilla in the main cluster of established eelgrass. You see it around patches of eelgrass, but well established eelgrass outgrows nascent hydrilla.

Lyngbya

The fourth and final invasive aquatic plant is lyngbya. Lyngbya, unlike the other plants discussed, is native to Florida. It had been the worst invasive aquatic plant in Crystal River for years, but it can’t tolerate saltwater. As saltwater intrusion increased from hurricanes and the lowering of the freshwater aquifer, lyngbya levels decreased. (For more on saltwater intrusion click here.) Lyngbya is now mainly found in Hunter’s Spring.

Lyngbya grows by attaching to other seagrasses and rocks on the riverbed. When mature, trapped gas in the lyngbya mats forces the invasive plant to the surface (see image above). Once on the surface, lyngbya blocks the sun from reaching the native eelgrass on the riverbed. Like the other invasive plants, lyngbya can also be spread in the ballast of a boat.

How To Combat Lyngbya

The most effective way to counter lyngbya is by planting eelgrass. This is exactly what Save Crystal River hopes to accomplish by planting eelgrass. Once the eelgrass matures, it outcompetes lyngbya. This forces lyngbya to the surface prematurely and forces the invasive plant out of the springs. The more eelgrass we have, the less lyngbya we have.

Unlike hydrilla, water hyacinth, and water lettuce, Manatee won’t eat lyngbya because it is slightly toxic. This means it’s up to us to make sure our waterways are clear.

While there’s not much we can individually do to eliminate these invasive aquatic plants, be careful not to transfer them to a new waterway. Clean kayaks, boats, paddleboards and any other mode of water transportation before traveling to a new location.

I’ll see you on the water,

Walker A. Willis

Photo Credits:

Hydrilla Underwater: My Canyon Lake

Water Hyacinth: The Tehran Times

Water Lettuce: Gardening Know How

Hydrilla in Hand: Noble Research Institute

Hydrilla Invasion: Stop Aquatic Hitchhikers

Lyngbya: Naturalake Biosciences