There’s one main reason Crystal River has become saltier: saltwater intrusion. If saltwater intrusion is what’s happening, the next logical question is why is it happening? The “why” comes down to one simple factor: overuse and abuse of the Floridan aquifer.

The Aquifer

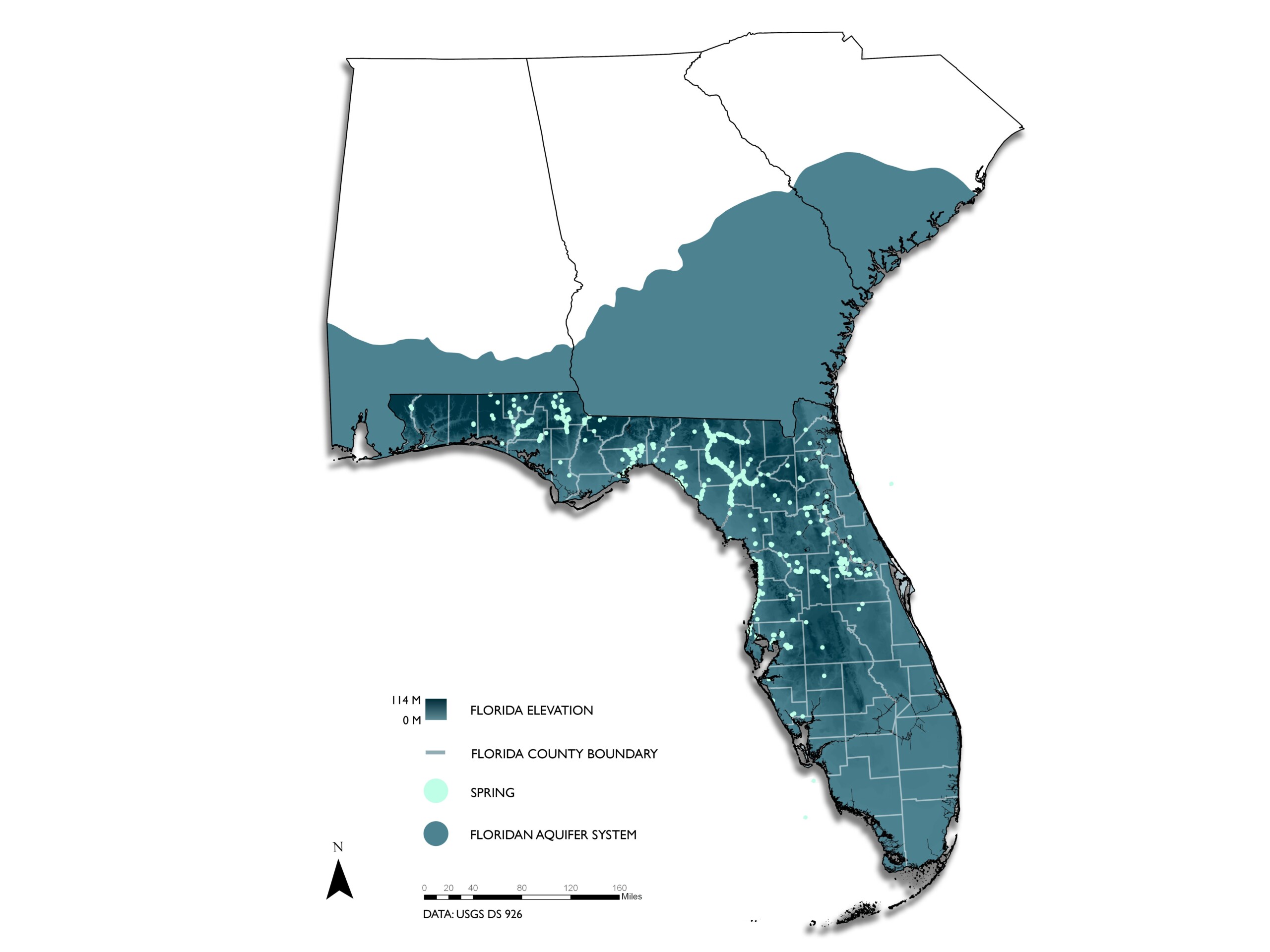

Before continuing, there are some key ideas to understand about Florida’s groundwater. According to the United States Geological Survey, the Floridan Aquifer spans approximately 100,000 square miles. That means it covers the entire state of Florida and parts of Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina (see image above). Our aquifer is one of the most productive aquifers in the world. According to National Geographic, “of the seven billion gallons of freshwater used daily across Florida, . . . most is taken from the Floridan aquifer.” (For more information click here.)

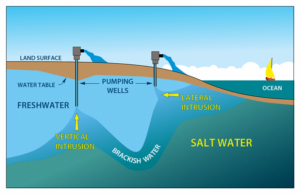

Even though the aquifer is abundant, just under the freshwater aquifer, there is a saltwater aquifer constantly pushing up against the freshwater aquifer (See image below). As developments pump freshwater out of the aquifer, the saltwater aquifer seeps into the freshwater laterally and vertically, which contaminates the freshwater.

Salts in Nature

For clarification, whenever I refer to “salinity,” “salt,” or “saltiness” in this post, I am referring to the compound NaCl, or table salt. While NaCl is not normally lethal to humans, it can ruin drinking water, kill freshwater aquatic life, and devastate freshwater ecosystems. There are chemical salts found in nature, but they are more likely to be considered pollutants than salts. Some chemical salts are even beneficial to ecosystems. For example, the salt calcium carbonate is the main component in pearls and the shells of marine organisms.

Initially, one might think aquifer depletion is a natural phenomenon, but in reality people cause the depletion problem. The aquifer, if unused for irrigation or drinking water, would replenish itself naturally and remain fresh. While it might be environmentally beneficial to leave the aquifer alone, the aquifer has become an integral part of our everyday lives. In fact, studies estimate that Floridians use 158 gallons of water a day per person. According to Craig Pittman, water pumped from the aquifer from 1970 to 1995 increased by more than fifty percent. By 2005, almost 4.2 billion gallons of water were pumped out of the aquifer per day.

Sinkholes

A major problem caused by draining the aquifers are sinkholes. You’ve probably seen news segments where whole houses or cars are swallowed by sinkholes. While these are some of the more extreme examples of what can happen, they are a reality directly caused from draining the aquifer.

A sinkhole occurs when the land above an underground cavity collapses. When humans drain the aquifer, it leaves open space underground where the water drained from. Typically, groundwater supports the earth above it, but without the water the land weakens and is susceptible to collapse. The correlation between sinkholes and draining the aquifer is why we see so many sinkholes in areas that require heavy irrigation, like farms, ranches, large grassy sports fields, and residential areas. A study back in 1982 conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey concluded that there was a direct relationship between the number of sinkholes and the draining of the aquifer, specifically in the Tampa Bay, FL area. While this study was almost forty years ago, it’s discoveries hold true today. Few actions have been made to course-correct overusing the aquifer, and today Florida still favors development over environmental health.

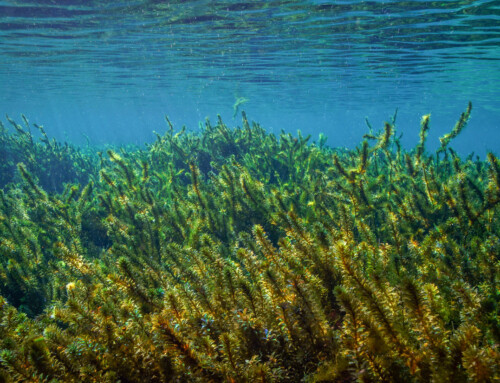

As groundwater lowers, it not only leads to sinkholes, but it also slows spring outputs. With less groundwater, there is less pressure forcing the water to the surface. If the groundwater gets too low, springs will stop releasing freshwater entirely. This is why we have seen springs disappearing all across Florida, especially in heavily populated areas.

How does draining the aquifer affect Springs?

In an earlier post, I wrote about how springs form. You can check that post out here. The simple summary is that a spring is a crack in the earth that allows water from the aquifer to seep up to the surface level. The only reason groundwater comes to the surface is because the water has nowhere else to go. As the aquifer fills, there is less and less space for the water, so the pressure grows. Eventually, the pressure forces the water towards the surface where it can escape in bubbling springs.

While Crystal River is still full of gushing spring vents, it is a trickle compared to the water production just 50 years ago. That’s why my father, as a boy, remembers Crystal River as a clear, cold river, teeming with freshwater fish. Hundreds of springs stopped venting groundwater, and there is less freshwater to push out the salty Gulf water that comes into Crystal River with each tide.

Save Crystal River has done a great job in opening covered spring vents. Even though this helps clear the salt water out of the river, the Florida Geological Survey concluded that Florida Springs have begun to release saltier water due to saltwater intrusion in the freshwater aquifer itself. Since people continue to drain our freshwater aquifer, the deeper saltwater aquifers are seeping up and contaminating the remaining freshwater.

What can we do to correct saltwater intrusion?

Currently, there is no easy solution for correcting saltwater intrusion once it takes place. The only real solution is to restore the freshwater aquifer. Restoration of the Floridan aquifer means people would have reduce the amount of water they use and allow rainwater to seep through the ground and reenter the aquifer. Groundwater replenishment is a much more difficult process than many think. Here is a source if you’d like to learn more: Groundwater Replenishment. It’s much easier to properly manage water usage in the first place than to correct water misuse.

I’ll see you on the water,

Walker A. Willis

Photo Credit:

The Floridan Aquifer Range: The Blue Water Audit

The Saltwater Intrusion Diagram: St. Johns River Water Management District